When we think about medical education, topics like anatomy, pharmacology, and patient care usually come to mind. But one crucial area often gets overlooked: medical writing and publication ethics.

Why should a busy medical student or a young doctor care about this? After all, isn’t research integrity something only professors or journal editors worry about? The truth is, ethical publishing isn’t just about avoiding plagiarism; it’s about building a foundation of trust that underpins the entire medical profession.

Why Start in Medical School?

We’ve all seen headlines about retracted studies or research misconduct. One of the most infamous cases, the fraudulent study that falsely linked vaccines to autism fueled vaccine hesitancy worldwide and lead to real harm.

When research goes wrong because of ethical lapses, the ripple effects can be devastating. Patients suffer when clinical decisions are based on flawed or manipulated data. When misconduct is exposed, careers can be ruined. Even worse, trust in science suffers, a loss we cannot afford during global health crises.

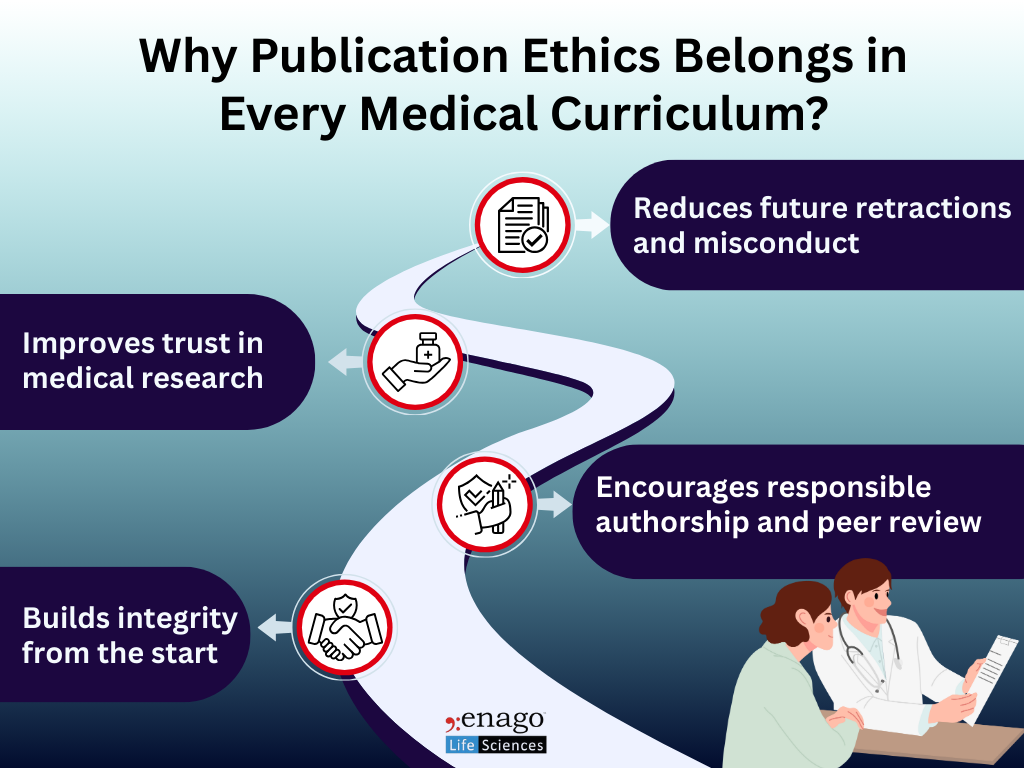

Publication ethics is often taught reactively, that is, when someone submits a paper and an issue pops up. But by then, habits (good or bad) are already formed. Introducing publication ethics and medical writing early helps future doctors:

- Develop professional writing skills to clearly and responsibly communicate science.

- Understand plagiarism and self-plagiarism.

- Maintain data integrity, no cherry-picking, no selective reporting.

- Recognize what qualifies someone as an author (and what doesn’t).

- Disclose conflicts of interest transparently.

Medical students are tomorrow’s researchers, reviewers, and policymakers. If they internalize these values early, they’re far less likely to make mistakes later.

A Tiered Approach

Not all students need the same level of training at the same time. A tiered model makes the learning process more relevant and sustainable:

Undergraduate level: Introduce the fundamentals—understanding plagiarism, referencing skills, principles of authorship, basics of research writing, and why data integrity matters. Students can be exposed to simplified case discussions and short reflective exercises.

Postgraduate level: Build on that foundation with advanced training—navigating complex authorship disputes, managing multicenter collaborations, disclosing competing interests, handling rejected manuscripts, and ethical issues in preprints, open peer review, or AI-assisted writing. PG students can also engage in simulated peer review and manuscript preparation workshops.

This stage-wise progression ensures that learning is context-appropriate, practical, and reinforced at key career milestones.

What Does Good Medical Writing and Ethics Education Look Like?

The pressure to “publish or perish” is real, yet publication ethics remains a blind spot in many medical schools. Faculty often lack formal training, and students graduate without fully grasping the ethical dimensions of research and authorship. When curricula treat ethics as optional, dangerous gaps emerge that can erode trust in science and ultimately harm patients when flawed research informs clinical practice. Addressing these issues requires more than token lectures.

So what would a future-ready, globally aware, and practice-oriented syllabus actually look like? It doesn’t have to be dry or preachy. In fact, the best programs are interactive:

- Move beyond single lectures to longitudinal teaching that spans from preclinical years to postgraduate training by embedding it across the curriculum.

- Use case-based learning to analyze retraction notices, authorship disputes, or high-profile misconduct cases to illustrate consequences.

- Use scenario-based evaluations, peer review simulations, or reflective assignments to measure competence.

- Invest in faculty development programs to ensure educators have both the knowledge and tools to teach publication ethics effectively.

- Leverage existing frameworks like COPE, ICMJE, and WAME and introduce students to these resources early. Invite editors or experienced researchers to share evolving best practices.

- Address grey zones like preprints, open peer review, and AI-assisted writing to prepare students for evolving realities. Discuss how tools like ChatGPT can be used responsibly and the risks of undisclosed or inappropriate use.

When students see how these issues play out in real life, ethics stops being abstract and starts being practical.

Building Trust from the Ground Up from Curriculum to Culture

In a world where misinformation spreads faster than ever, ethical literacy is essential. Medical schools and residency programs can partner with journals to co-host workshops or webinars on ethical publishing. Institutions need clear policies, faculty development, and experiential learning that goes beyond theory. Embedding publication ethics into the core curriculum, backed by assessment and institutional accountability, sends a powerful message: integrity matters as much as intellect. Sharing COPE case studies, developing localized resources, and making policy compliance part of graduation requirements can strengthen the message. However, real adoption requires overcoming faculty shortages, resource limitations, and resistance to curricular change.

At its core, medicine is about trust. Patients trust doctors with their lives. Doctors trust research to guide their decisions. And society trusts the medical profession to uphold the highest standards of honesty and accountability.

By teaching publication ethics, medical schools can prepare students to uphold the integrity of their profession. That’s an investment in better research, better medicine, and ultimately, better patient care.

It’s about time we treated publication ethics with the same seriousness as anatomy or pharmacology because the consequences of ignoring it can be just as life-changing.

References

- Bandyopadhyay, Ujjwal, Ranjana Bandyopadhyay, and Abhay Mudey. “Teaching Medical Ethics and Professionalism to Undergraduate Medical Students in an Innovative Way.” Journal of Evidence Based Medicine and Healthcare 8, no. 17 (2021): 1139–45. https://doi.org/10.18410/jebmh/2021/220

- Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), Open Access Scholarly Publishers Association (OASPA), and World Association of Medical Editors (WAME). “Transparency & Best Practice – DOAJ.” Last modified September 14, 2022. https://doaj.org/apply/transparency/.

- Dyer, Clare. “Lancet Retracts Wakefield’s MMR Paper.” BMJ 340 (February 2, 2010): c696. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c696

- Hays, Richard, and Ken Masters. “Publishing Ethics in Medical Education: Guidance for Authors and Reviewers in a Changing World.” Perspectives on Medical Education9, no. 2 (2020): 68-75. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10697547/.

- Leapman and Moe, “Research Ethics and Medical Education,” Virtual Mentor 6, no. 11 (November 2004): 494–96.

- Masic, Izet, Ajla Hodzic, and Smaila Mulic. “Ethics in Medical Research and Publication.” Materia Socio-Medica26, no. 2 (2014): 141-145. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4192767/.

- Moreira F, Teixeira P, Leão C. Effectiveness of medical ethics education: a systematic review. MedEdPublish (2016). 2021 Jun 15;10:175. doi: 10.15694/mep.2021.000175.1. PMID: 38486576; PMCID: PMC10939587.

Author:

Rebecca D’souza, PhD.

Associate Content Expert, Enago Academy

Connect with Rebecca on LinkedIn