The medical writing domain has expanded beyond drafting regulatory documents or journal manuscripts in English. It now serves diverse populations across geographies, languages, cultures and health-systems. For writers and communicators in global health, embracing cultural and linguistic nuance is essential to ensuring scientific accuracy, ethical integrity, and equitable access to health information.

Why Inclusive Medical Writing Matters

Three inter-linked drivers make inclusive medical writing urgent in global health.

1. Linguistic Access & Equity

Although English is the primary language of only about 5% of the global population and second language for less than 20%, it dominates scientific publication and medical education. A recent article published in BioMed Central documents how the hegemony of English in global medicine disproportionately affects many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and hinders access to health information in local languages.

When patients cannot access medical information in their native or preferred language, comprehension suffers and adherence to treatment or public-health advice may decline. For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic, English-only vaccine information in India led to confusion and misinformation among rural populations. When local governments began issuing multilingual, plain-language guides, vaccine hesitancy rates dropped significantly.

2. Cultural Relevance and Trust

Language is tightly bound to culture: the words we use, the metaphors we choose, the assumptions we make. In global health communications, authors must recognize that texts carry cultural meaning are sometimes unintentional. Take the example of diabetes education programs in Latin America: early materials translated directly from U.S. resources used food examples like “whole-grain bread” or “peanut butter sandwiches.” These were unfamiliar to local audiences. When nutritionists revised them with culturally relevant foods—like corn tortillas and plantains—patient engagement and adherence improved dramatically.

Therefore, if a medical-writing document is insensitive to the cultural context of the audience, it may not only fail to engage but may inadvertently reinforce power imbalances or biases.

3. Inclusive Language as an Ethical Imperative

Inclusive language is linked to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in publishing and healthcare communication. A review of author instructions in highly cited medical journals found that only 23% gave guidance on inclusive language, highlighting a major gap.

Using language that respects identity, culture, gender, socioeconomic status, disability and ethnic background is increasingly regarded as best practice—not a “nice-to-have.” By adopting inclusive medical writing, we serve not only better science but better health outcomes and more equitable communication.

Key Dimensions of Cultural and Linguistic Nuance

To deliver inclusive medical writing in global health, writers must attend to three overlapping dimensions: language choice, audience literacy and cultural context.

1. Language Choice and Translation

- Using plain language or translation into locally spoken languages improves comprehension. As one commentary argues: “the languages we choose to use as global health practitioners shape power dynamics, determine whose voices are heard, and impact the effectiveness of our actions.”

- Attention to translation strategy matters, as literal translation may preserve technical accuracy but fail in achieving cultural relevance. For example, a study on translation of patient-information leaflets into Urdu found that paraphrasing, restructuring and region-specific terminology improved readability and adherence.

- Since many patients and health-system actors operate in more than one language, writers must decide whether to produce bilingual materials, accommodate local dialects, or partner with interpreter/translator teams.

2. Audience Health-literacy and Contextual Background

- Even when writing in a shared language (e.g., English), the audience’s health-literacy level, familiarity with biomedical concepts, and cultural background can vary significantly. Writers should simplify technical language where appropriate, avoid jargon, clearly define terms, and use culturally meaningful examples. For instance, even translated materials may fail if local dialect, idiom, or literacy level is not considered.

- Awareness of local practices, beliefs and preferences matters. A one-size-fits-all English text developed for a Western audience may require adaptation for an LMIC setting or for a community with strong indigenous knowledge systems.

3. Cultural Context, Power Dynamics, and Inclusive Framing

- Inclusive writing means more than translation; it means framing research, evidence or health guidance in ways that respect and recognize cultural identities and knowledge systems. Writers must avoid “othering” (treating different cultures as exotic or deficient) and adopt a respectful, collaborative tone.

- Engaging local collaborators and stakeholders is key. Local voices bring cultural insight and help ensure the writing reflects the lived realities and expectations of the target audience.

Practical Steps for Inclusive Medical Writing

Here are actionable strategies that medical writers, editors, and global health communicators can adopt to address cultural and linguistic nuances effectively:

1. Conduct Audience Analysis

Before writing, identify who the audience is: language(s) spoken, literacy levels (both general and health-specific), cultural norms, beliefs about health, prior experience with biomedical communication. This analysis helps tailor tone, terminology and complexity.

2. Adopt Inclusive Language Guidelines

Use person-first language (e.g., “people living with diabetes” rather than “diabetics”), avoiding stereotypes, avoiding deficit language (“vulnerable population” may imply inferiority), and choosing respectful terms for culture, ethnicity, gender identity, disability, etc.

3. Simplify and Localize Content

Use plain language where possible; define technical terms. Use culturally relevant analogies, examples or case studies. Translate materials into local language(s) or dialects as needed, engaging native-speaking subject-matter experts. Moreover, ensure translation is not purely literal—cultural adaptation may require restructuring or choosing region-specific idioms.

4. Collaborate With Local Stakeholders

Engage local health-system professionals, translators, community representatives, and subject-matter experts. Their insight helps ensure cultural validity (e.g., what wording resonates? what concept may be misunderstood?).

5. Review and Revise Iteratively

Use peer review that includes diverse cultural and linguistic perspectives. Ask for readability testing among members of the target audience. Lastly, monitor feedback from readers regarding comprehension, clarity and cultural relevance and use this to refine future writing.

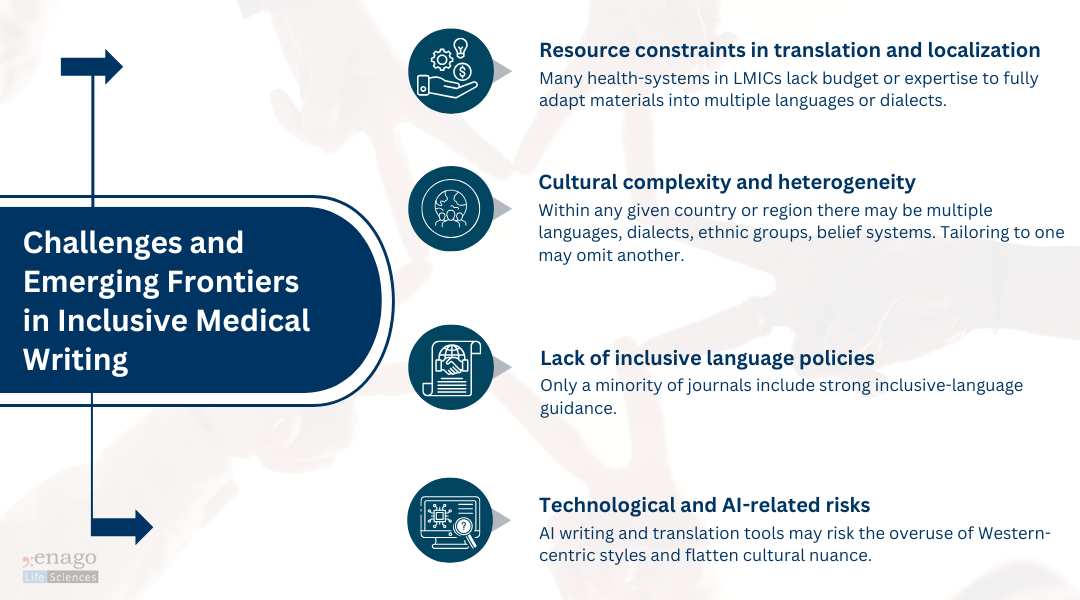

Nevertheless, these challenges also present opportunities. As we develop “language-concordant” health materials and build culturally aware writing teams, we improve not only the reach of health communication but also its equity and fairness.

Nevertheless, these challenges also present opportunities. As we develop “language-concordant” health materials and build culturally aware writing teams, we improve not only the reach of health communication but also its equity and fairness.

Expanding the Lens: Institutions, Publishers, and AI

While writers play a frontline role, inclusive medical communication requires systemic support. Institutions, publishers, and technology developers must also take responsibility.

Institutional and Publisher-Level Policies

Many leading organizations are now recognizing this gap.

- The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE), the International committee of medical journal editors (ICMJE), and STM Association encourage journals to include inclusive language policies in author guidelines.

- EASE (European Association of Science Editors) recommends explicit editorial standards for linguistic and cultural sensitivity.

- Major publishers, such as Elsevier and Springer Nature, have begun incorporating diversity and inclusive communication checklists into their manuscript submission systems.

However, policy uptake is uneven. Some journals require plain-language summaries or translations, while others leave it optional.

True inclusion will require:

- Multilingual publishing support, especially for abstracts and lay summaries.

- Training for editors and peer reviewers to detect cultural bias or linguistic exclusion.

- Equitable authorship models, encouraging participation from LMIC researchers who often face language barriers.

The Emerging Role of AI in Inclusive Writing

AI-driven writing tools are reshaping how health communication is created, reviewed, and translated. While human empathy and cultural understanding remain irreplaceable, AI can augment inclusion in several ways:

- Real-Time Translation and Localization

Tools like Google’s medical translation API now integrate medical glossaries and cultural variants, enabling more accurate local-language communication. However, human validation remains critical to avoid nuance loss or mistranslation. - Bias Detection in Text

Emerging AI tools like Trinka’s inclusive language checker can flag gendered, stigmatizing, or culturally insensitive terms. These tools help writers self-audit tone and ensure linguistic equity before publication. - Readability and Comprehension Analysis

AI can assess readability levels to align materials with audience literacy, particularly in patient-facing documents. This ensures plain language is maintained without oversimplifying scientific rigor. - Multilingual Data and Voice Inclusion

Training AI models on diverse linguistic datasets reduces bias and improves understanding of idiomatic expressions across cultures.

Still, these technologies must be guided by human expertise, ethical oversight, and culturally informed datasets. As AI becomes a writing partner, the goal isn’t automation — it’s augmentation: supporting writers to communicate with more empathy, precision, and reach.

By systematically analyzing who we are writing for, adopting inclusive language, localizing content, collaborating with stakeholders, and continuously learning and adapting, we can produce medical writing that honors diversity and advances health for all. In a world where health crises and scientific discovery cross borders, the words we choose and the languages we use matter more than ever!

Author:

Anagha Nair

Editorial Assistant, Enago Academy

Medical Writer, Enago Life Sciences

Connect with Anagha on LinkedIn